Why what we eat matters for forests

What we eat is connected to forests through land. Food demand shapes how land is allocated, which ecosystems are protected, and where agricultural frontiers expand. This does not mean individuals “cause” deforestation on their own—food systems are driven by infrastructure, prices, access, culture, and policy. But it does mean that everyday consumption can either increase or reduce pressure on land. If you want to convert personal awareness into collective action with measurable outcomes, Donate to support verified forest restoration.

2. The scientific connection — Diet → land use → deforestation → climate

The link between diet and forests is fundamentally a land-use equation. When demand rises for land-intensive foods, the system often responds by expanding cropland and pasture. That expansion can displace forests and other natural ecosystems.

- Agricultural and livestock expansion: Crops require land; livestock requires land directly (grazing) and indirectly (feed crops). In many contexts, higher demand for animal-source foods increases total land demand across supply chains.

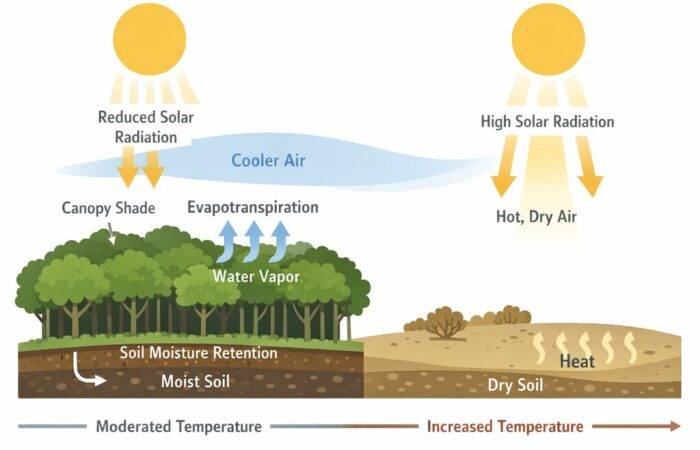

- Pressure on forest ecosystems: Forests are not “unused space.” They regulate water cycles, protect soils, and support biodiversity while storing large carbon stocks. When forests are converted or degraded, these functions decline—locally and globally.

- Emissions from land-use change: Converting forests to agriculture releases carbon stored in trees and soils. These emissions can be immediate and significant, making land-use change a central driver of climate impact alongside agricultural methane and nitrous oxide.

This is why reducing the food footprint is not only a nutrition issue—it is a land-use and deforestation issue.

3. What you can actually change — Practical choices without blame

Individuals cannot redesign the food system alone, but three levers are realistically under personal control:

a) Dietary choices (feasible, not extreme): Small, consistent shifts can reduce land pressure—such as moderating land-intensive foods, diversifying protein sources, and choosing lower land-footprint options when accessible. The goal is practicality, not perfection.

b) Food waste reduction: Wasted food carries the full land, water, and emissions footprint of production without delivering nutrition. Planning purchases, using leftovers, and improving storage reduces unnecessary demand—and therefore land pressure.

c) Food origin and traceability: When options exist, prioritizing more transparent sourcing can reduce deforestation risk. Claims should be treated cautiously unless supported by credible evidence and accountability mechanisms.

These actions matter, but they are most effective when paired with restoration that addresses degraded landscapes and strengthens rural resilience.

4. The role of restoration — Why restoring forests must accompany consumption change

Even if diets improve and waste declines, vast areas remain degraded from decades of land conversion. Forest restoration complements consumption change by rebuilding ecosystem functions: carbon storage, water regulation, soil stability, and biodiversity connectivity. High-integrity restoration is not a symbolic “tree count.” It requires appropriate ecological design, long-term maintenance, and local stewardship—so restoration outcomes persist over time rather than disappearing after the photo moment.

5. Transparency and MRV — How to verify restoration is real

Public skepticism is reasonable: many climate claims are vague, unmeasurable, or based on weak monitoring—creating the risk of greenwashing. That is why restoration credibility depends on MRV (Measurement, Reporting, and Verification). MRV combines field monitoring (survival, growth, species composition), geospatial evidence (remote sensing), and transparent reporting so stakeholders can confirm that restoration occurs in the right place, at the right scale, and over time.

To see how verification strengthens integrity and prevents empty claims, See how MRV evidence prevents greenwashing.

6. Rural benefits — Jobs, soils, and resilience in the Amazon and Andes

When designed responsibly, restoration is also rural development:

- Paid local employment: Restoration creates sustained work—nursery production, planting, maintenance, monitoring, and protection—when financing supports multi-season implementation.

- Improved soils and water: Restored forest cover and buffers reduce erosion, improve infiltration, and stabilize watershed function—supporting agriculture and community water security.

- Productive resilience: Healthier landscapes reduce vulnerability to droughts, floods, and climate variability.

These benefits are directly relevant for Shipibo communities in the Amazon, where forest integrity supports watershed stability and territorial sustainability, and for Andean highland communities, where soil and water regulation are critical for resilient livelihoods. The point is not to romanticize communities, but to recognize restoration as a practical pathway to stronger rural systems when it is fairly compensated and technically verified.

Better food choices and lower waste reduce pressure on land and forests—but they cannot restore degraded ecosystems alone. Verified restoration turns individual intent into collective, structural action with measurable outcomes.

Donate to convert individual changes into verified forest restoration and real benefits for rural communities. Your donation complements personal choices, supports collective impact at landscape scale, and is backed by technical verification.